How Unusual Pricing Can Slow Sales

One of the strangest promotions I’ve seen in a long time is buying a drink at McDonald’s for one dollar. The kicker is that you choose the size without the price changing. Would you like a small or a large for one dollar?

One conversation went like this:

I’ll have a small Coke.

The person’s friend whispered, They’re all one dollar. Get a large.

No, a small is fine. I’m not that thirsty.

Soda calories and waste notwithstanding, the person could have saved part of her drink for later. She also could have shared some of her drink with her companion. Or she could have simply asked for the large size in case she turned out to be more thirsty than she anticipated.

The bigger point is this: a moment of wary hesitation is caused when pricing doesn’t seem intuitive to a purchaser as they scan the offer for a hidden catch. The McDonald’s offer is strange and its results are a marketing psychology paper waiting to be written.

I saw the same phenomenon at online grocer Peapod. As grocery shoppers, we’re conditioned to understand that a larger bulk size often results in a lower unit price. That’s been a retailing axiom for decades and created the rise of the warehouse superstores.

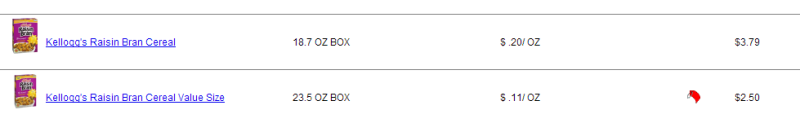

But on this particular day, the larger size was once again less expensive than the smaller size. As you can see below, the unit cost for a larger box of Raisin Bran was lower as one would expect. This difference was so great, however, that anyone buying a smaller box was paying a premium at the unit cost level and at the total price level.

Almost no one understands that without first thinking about the issue.

Buying an extra 4.8 ounces of cereal (25% more) reduced the total cost by $1.29 (34%). And that just doesn’t make sense to people. We understand that the unit cost is and should be lower, but the 45% decrease made buying more cost less.

There was undoubtedly a good reason for this price just as there are reasons why someone might prefer a box of cereal that is 25% smaller. You’ve already thought of several reasons for both when you read that sentence.

And that’s the problem.

Pricing should never make someone think, “Why is this deal different than the pricing I’ve come to expect?” More of something does not normally have a total cost lower than less of something. Yet that’s exactly what happened. At least the drinks were the same price for a larger size. The cereal actually cost less.

Your takeaway as a business leader is that pricing outside the norm of expectations without an explanation leads to hesitation when a prospective buyer searches for a hidden gotcha. That kind of pricing slows and possibly risks the entire sale because anything unexpected slows down a sale.

I understand when the local bakery posts a sign late in the day that says “Oops, we baked too much” or why Broadway-savvy theatergoers buy tickets the day of their show. Those are norms we’ve learned as American consumers.

Ask someone unfamiliar with your pricing strategy to see if they can look at your prices and articulate your pricing strategy. If they can’t, you’ve got a potential sales objection that may leave prospects wary of doing business with your organization.